A Water from the Well blog post, Parashat Vayigash

Written by Rabba Kaya Stern-Kaufman

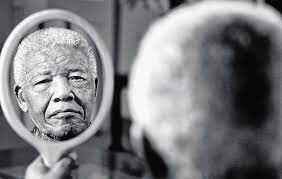

Dedicated to Nelson Mandela, who passed from this world on 3 Tevet (December 5, 2013).

Like Joseph, who spent 20 years imprisoned in Egypt, Nelson Mandela spent a total of 27 years in prison. Like Joseph, after his release from prison, Mandela was raised up from the lowest place in society to the highest, becoming president of South Africa. Like Joseph, Mandela transformed his land and saved his people. Like Joseph, he forgave his oppressors and forged a new relationship with them outside of the dynamic of victim and oppressor.

When asked about his remarkable capacity to forgive his oppressors, Mandela offered many responses, including these two statements:

People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.

As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.

This week’s Torah portion opens with the verse: vayigash Yehudah, vayomer bi adoni, literally translated as: Judah approached (Joseph) and said, “Please My Lord… (Gen. 44:18). This is the beginning of a speech in which Judah begs the viceroy (not recognizing his own brother Joseph in the role) to take him as a slave in place of his youngest brother, Benjamin. In order to appreciate Judah’s words, we must first appreciate who Judah is.

Judah is the brother who originally proffers the idea of selling Joseph to the merchant caravan. He is responsible for Joseph’s descent into Egypt. Judah is also the brother whose personal story in connection with Tamar is interspersed through the Joseph narrative. Judah denies the rights of his daughter-in-law Tamar, but then recognizes his misdeeds. He takes responsibility for Tamar and makes things right. Traditionally he is viewed as the model of a ba’al teshuvah, a truly repentant person. Judah represents the capacity for personal transformation. He has the strength to own the truth about himself and to support justice, even if it means personal embarrassment.

It is after these events that Judah is able to take responsibility and ensure the life of his brother Benjamin, something he was unable to do for Joseph. He demonstrates his teshuvah, his personal transformation, through his willingness to give over his own life in exchange for Benjamin’s freedom. And by doing so, by offering to sacrifice his own freedom, he calls Joseph out from his disguise, out of his own prison of sorts.

Vayigash Yehudah– Judah comes close to Joseph.

The Or HaHayyim (18th century Torah commentator) asks the question: Why is this phrase needed?

We know that Judah was standing close to Joseph when he spoke to him.

Or Hahayyim explains: he drew close to him within his heart. He drew close to this Egyptian viceroy who held their lives in his hands. He drew close (to him) in his heart, truly loving him, so as to arouse compassion within him.

“As face answers to face in water, so does one man’s heart to another.” (Prov, 27.19)

The Vitebsker Rebbe teaches on this principle, that in all situations we have the possibility of discovering an aspect of ourselves. Judah did not know he faced Joseph, yet he found a way to bring his heart near to this man who appeared as his oppressor. When Judah states: bi Adoni (commonly translated as Please, My Master), he is really saying: “My Lord is in me.” You are in me. I am connected to you and you to me in a most essential way.

Vayigash Yehudah bi Adoni- And Judah came close and said, You are in me.

Your struggles are my struggles.

Your failings are mine as well.

Judah, the forefather of mashiach (the Messiah) and the symbol of redemption, is not only the ba’al teshuvah, the one who repents for his actions against Tamar and against his brother Joseph. He is the one who finds a way to connect his heart, even with one who is his oppressor. He finds the Divine root of compassion in himself and he arouses it in Joseph, thus causing Joseph’s armor to dissolve. Joseph can no longer maintain the ruse. And a flood of tears emerges from Joseph’s heart.

Joseph could no longer control himself before all his attendants, and he cried out,”Have everyone withdraw from me!” So there was no one else about when Joseph made himself known to his brothers. His sobs were so loud that the Egyptians could hear…” (Gen. 45:1-2)

In this Torah portion we see that it takes two to bring about a true healing.

Joseph is disarmed and thus, like Judah, he too is able to step outside of himself, out of his own personal story and see the bigger picture. He responds to Judah:

Now, do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me hither; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you…God has sent me ahead of you to ensure your survival on earth, and to save your lives in an extraordinary deliverance.

(Gen. 45: 5, 7)

Throughout this portion, Joseph states this idea three times. He affirms that nothing is as it seems, when viewed from the most expanded awareness. Joseph humbles himself before God and his brothers. He does not cling to the personal wrong perpetrated against him. He sees the divine hand in his life and it is this broad perspective that enables him to forgive. Both Joseph and Judah are able to transcend their personal pain for the sake of the greater good.

Our Torah delivers the message that healing from painful interpersonal conflict is possible and that the potential for redemption is in our hands and hearts. It requires two elements.

The Judah principle: An expanded heart: I recognize my responsibility for all my brothers, and I am able to connect my heart with others who are also in pain, even if they appear as my oppressors. In reality, they, too, are my brothers.

The Joseph principle: An expanded consciousness: I do not need to see myself as a victim. Rather, I can let go of my personal wound because I understand that I am a participant in a greater story. By connecting myself to the greater mystery of life unfolding, I can serve in the process of a greater redemption.

As Nelson Mandela once said: A good head and a good heart are always a formidable combination.

Vayigash Yehudah: And Judah came close, close to his brother Joseph whom he had wronged. Though he didn’t know he was his brother, he came close anyway. And he said, Bi Adoni– My Lord is in me. You are in Me.

We are all brothers and sisters, thinly disguised as strangers. Can we see through the veils? And even if we cannot, can we, like Judah, still come close to recognize that, despite our apparent differences, You are in Me, as I am in You?